How to get the most out of your next tech test

I was recently searching for a new job, which meant I got to experience many of the weird and wonderful (and some downright awful) ways that software companies try to vet prospective employees.

One of those ways is via a tech test, and I have done a fair few of those in this interview cycle and previous ones. I actually enjoy… some of them. Some are so dull that I often will never get around to attempting them if I have multiple applications on the go. Some require things which I have never come across before and I love how much I get to learn from them. Some accurately reflect the sort of work I would be doing at the company (I recommend always asking this) and therefore help paint a fuller picture of what I would be getting into. Some ask for such a ridiculous amount of work in an equally ridiculous timeframe that it is all I can do to not respond “lolnope” when I tell them I won’t be continuing with their (dumbass) process.

Many of us have thoughts and feelings on the value of tech tests as a suitable screening mechanism for engineering candidates, and this post is not going to go into that. This is also not a “My First Tech Test” post for those who are new to the game (if you’d like one of those, ping me an email and I will see what I can do). This post covers the things that some people neglect to do beyond solving the problem.

If you are lucky, the company you are interviewing for recognises that a tech test is only part of a wider process, and only a small part at that. Hopefully the challenge you are facing is reasonably scoped, and is not some points-based, soulless pass/fail HackerRank or Codility algo exercise.

If that is the case then yay! This means that simply making your tech test “pass” is not the end

goal: a tech test allows you to show so much more than whether or not you know how to google solve algorithms.

A tech test, done right, allows you to make a real impression.

TOC

- Who is reviewing your test?

- Read the spec

- Planning

- Naming your repo

- Tests

- Commits

- KISS

- Linting and formatting

- Attention to detail

- Tools

- Documentation

- Final checks

Who is reviewing your test?

You are! Okay, not really you, but people like you: engineers. If a company is going through a growth spurt, then it becomes almost everyone’s job to get involved with bringing in some new blood. The tech tests I have reviewed vastly outnumber those I have submitted as part of my own interview processes, and most of what I have learned about doing a good job on them comes from being on that side.

If being on the other side of the process isn’t something you’ve done before, maybe you’ve never felt comfortable or qualified to judge others’ work, or maybe you’re a brand new Junior (Hi there! You’ll be fine!), you still probably have a subconscious feel for a candidate who is proud of their work.

(As an aside, I always encourage my juniors to get in on interviewing prospective candidates. It is a great way to learn, plus if I am looking for someone to join the team I tend to want to involve the team in that decision: Juniors definitely included.)

Whatever your experience, you can use your awareness of what you like about others’ projects and code to guide your instincts. You know what it feels like to come to a new repo and think “huh, this is nice”, which means you know the little touches which will, at the very least, put your reviewer in a good mood, and at the most make them see that you would be a cool person to work with.

Two important things to remember about your reviewers:

- Reviewing is not their only responsibility; they have likely carved out 30-60 mins of their day to review your code.

- While there is a bit of “box-ticking” (are there tests? does it run? etc), most of the assessment is very subjective.

It is therefore crucial to try not to actively piss them off by making reviewing your code harder than it needs to be.

So; the recruiter’s email has just landed in your inbox, let’s begin.

Read the spec. Read it again (and again, and again…)

You’d think this should go without saying, but ¯\_(ツ)_/¯.

One of the things I remember most clearly from doing school exams is my teachers telling us to read the papers, cover to cover while highlighting key words, before attempting to answer a single question.

The same applies here: before you even open your editor, read the spec as many times as it takes for you to really understand the problem you are being asked to solve, and to ensure you don’t miss any specific instructions. Write down some notes, start googling terms you don’t know, maybe even google the things you do know.

Beyond the core problem, are there any little things they would like you to take into consideration? Do they just want you to write code, or are there some open ended questions you will need to set aside some time for? Can you separate the things which matter to them from the filler?

It is stunning how many tests I have received where the candidate didn’t at least acknowledge all parts of the assignment. I am more than happy to accept a “sorry I ran out of time to do part X” (it is very hard to scope a test), but when I get a partially finished test with no explanation, I have no way of telling if they struggled for time or simply didn’t care enough to read the spec properly.

Planning

Another gem from my school days which I was happy to hear often when I started this career: 90% of the work is planning, 10% is writing (code in this case).

This is especially important if the test has multiple parts. Coming up with a plan will let you see how much time you will need to dedicate to each section.

In a tech test you can also use the plan to show your working. Write it up and commit it to your repo, along with anything else which shows your thought process.

As you start writing code, keep notes on problems you face and any changes to the plan you need to make. It doesn’t need to be a perfectly edited design doc (that would be very unreasonable in nearly all tech test timeframes), but just enough to show you aren’t winging the entire thing.

The added benefit of including a plan (even just a TODO checklist somewhere), is that if you do run out of time, you have still demonstrated knowledge of things that you didn’t quite get around to coding. If you mention these in your submission email, you can also set up some good topics of conversation for the follow up interview.

Naming your repo

If you are asked to submit your test as a public Github repo and you are NOT given a very

specific name, don’t put the company name in your repo name (tech-test-for-company-x or whatever).

Use the one Github suggests or be creative. Likewise, if you were not initially requested to

keep your work in a public repo but you want to move it there afterwards to be part of your profile,

take care to remove any mention of the company.

This helps ensure your test is not easily searchable, and consequently less copyable. Speaking of which: please don’t do that.

Tests

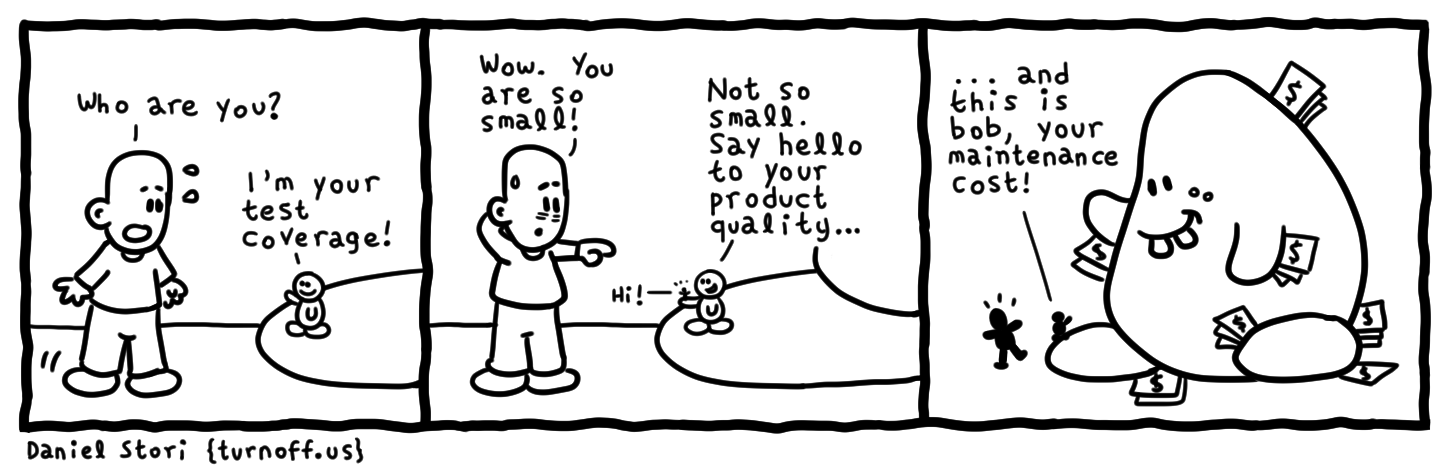

The first thing I do when I clone a candidate’s repo into the sandbox is run the tests. Then I look at the coverage. Then I read the tests.

You should always test your code anyway, but if the spec has explicitly stated they want to see tests then not writing tests is… inadvisable. Units, integration, everything. It clearly matters to the prospective company otherwise they would not have mentioned it.

I especially love acceptance-level tests because, if they are thorough enough, then I don’t even need to get the code running to know that it works: the tests do it for me! The luxury! I mean, of course I check the thing can build and stuff as part of the review, but the candidate has demonstrated that they understand the importance of fully automated end-to-end testing… and that they appreciate just how lazy engineers are. Do I want to manually build AND test stuff every day? Like some kind of sucker?! The person I want to work with is the person who saves me from that.

Remember to go beyond “happy path” cases. Test that it behaves well in the edge cases; test that it fails in the way it should. When it comes to unit coverage… honestly any number is fairly meaningless (except for 0% which definitely means something, and it is not good) Those of you who practice TDD will end up with 100% in the majority of cases without even thinking about it.

If you know how to, run all your tests in a clean environment (ie. in a Container). Provide your reviewers with a handy script so that they can also run your tests in a container with the image and settings you have been using.

“But Claudia! I only have N hours for this task and writing tests takes aaages!”

Firstly, you seem to think that checking and proving your code not only works, but works reliably and will continue to work even after changes and/or new features is somehow not important. It is. Secondly…

Pop quiz! Which candidate is moving to the next round?:

-

Candidate A submits a partially completed tech test, but all the code which does exist is thoroughly tested.

-

Candidate B submits test will all code written, but no tests. There is an apologetic note saying they meant to get to it.

Both versions of the test have only fulfilled half the requirements, but only one attempted everything asked for. A partially completed test which is proven to reliably do what it says it can, even if that featureset is smaller than asked for, is of greater value than a whole bunch of fragile, untested code. It is a matter of quality and care over quantity.

You remember above I said to at least not deliberately piss off your reviewer? Well, making me check that your code runs against a bunch of edge cases is… irritating. If I only have 30 minutes to review your test, is this really how you want me to spend that time? Honestly, I wont do that. If I come across candidates who submit zero tests, I will verify that the happy path is actually happy, and then send a follow-up email asking for some sort of proof that the program will not fall over the second that conditions become less than perfect.

Commits

We all get lazy with commits when working on our own stuff. I have many a repo

with a commit history full of "ffs", "please please why wont you work?!" and “omigod finally,

DON'T TOUCH THIS FUTURE CLAUDIA I MEAN IT”

But… this is a job interview: be professional!

You want to prove that you will be an easy person to work with. A person who is hard to work with will fill the codebase with obscure changes and no explanation why. Don’t be like that.

Here is an excellent guide for commit message etiquette. The author mentions the Linux kernel as an instance of exemplary commit history and I could not agree more. I have gotten to the bottom of many a kernel issue from reading commit messages alone.

Even if you have already filled your git history with trash, don’t worry! You can always go back and

clean it up with git rebase.

KISS

Something we have all heard before: Keep it simple, stupid.

If you are writing code with the objective of being as complex and clever as possible… well, there is no polite way to say this, but; you are doing it wrong. “But what if the problem is really complex?”, you ask. NOPE, the rule still applies: yes your code may be more complex relative to a problem with a simpler solution, but this doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t still strive for simplicity. In fact, if the problem really is that complex, then it is even more important that the solution isn’t a nightmare to parse (unless you really hate your colleagues and your future self).

In the context of tech tests, another way to put this is: Show off, but don’t show off.

Again: your reviewer does not have infinite time for your test. You want them to be able to understand and appreciate what you have done with minimal effort. You do not want them scowling at a single piece of unnecessary complexity for 10 minutes.

We endeavor to write simple code to be kind to ourselves and our colleagues. Since these are hopefully your future colleagues, now is a good time to be kind to them.

On a similar thread of simplicity, try not to go too far beyond the task’s requirements. It may be tempting to throw on a few extra bells and whistles, but don’t go crazy. Coming up with a tech test which doesn’t take a candidate forever to write and also doesn’t take your employees forever to review is really hard. Stick to the script, and keep the additional flair to a sensible minimum.

Linting and formatting

If the language you are testing in comes with standards for linting and formatting, follow them. If there are tools which will hand all the linting and formatting errors to you on a silver platter FOR FREE, use them!

It is… extremely disappointing to open up a candidate’s test in one’s editor and have it immediately light up with innumerable errors like this. Most of these errors will not be the end of the world (warnings about required comments, poor choice in variable name, etc), or will help with general forgetfulness (unused method), but some will highlight actual problems (unhandled errors). Juniors could be forgiven, but others should know better.

Attention to detail

In the same vein as the above, show that you take pride and care in your work by paying close attention to details.

- Ensure your variables and functions are clearly and consistently named

- Don’t leave random blank lines, unless they are there to aid in readability

- If you added print statements or commented out code while debugging, clear them away

- If you have to leave TODOs, explain why you couldn’t take care of it either in a comment or your Plan notes

… and other general “housekeeping”.

The superficial appearance of code matters as it helps make it easier to read. Leaving the place a mess tells the reviewer that either you didn’t bother to check through your work before you submitted, or that you did but you don’t really care.

Either way it doesn’t make a good impression and it’s kind of like showing up to a swanky office interview in your pajamas.

Tools

Providing some tooling which lets people build/run/test your program with a simple command is a very nice touch. It’s not (and shouldn’t be unless explicitly requested) a dealbreaker if a candidate doesn’t have one, but it is always appreciated and is a neat way to show off.

Personally, I love a Makefile, but shell scripts are common and some languages

have their own things going on.

Documentation

I cannot undersell how much difference a good Readme makes. I have put candidates through to the next round based principally on the strength of their docs.

Your Readme is the chance for you to show your care for quality; your communication style and skills; how you plan; your thought process; your attention to detail; your open source game; your respect for those interacting with your codebase; your markdown skills!

This is also one of your biggest opportunities to show your personality. For most of your future colleagues this is often the first contact they have with you, don’t waste it! Show your enthusiasm for what you learned and built. Crack some jokes!

At a minimum your Readme should have the following:

- Table of contents

- Summary of what the code is for/does

- Build/download/install instructions (if applicable)

- Deploy instructions (if applicable)

- Run instructions (if applicable)

- Usage options

- Test instructions

To go the extra mile you can add even more:

- Describe the technologies you used and why

- Give examples of how your program could be used, who may find it useful

- Give examples of how your code could be expanded

- Record a gif or video of you using the program

- Link to your CI pipeline

- If your directory structure sprawls a bit, note down where someone should begin navigating or highlight important files for them (if you need very detailed nav instructions for a tech test, you may want to consider how you got there)

- If any tech was new to you, write how you approached learning it and what your impressions are

You know how it feels when you go to a new project, you follow instructions, use some sample yaml (or whatever), run the example command and it just… works? That is the experience you want to provide. Don’t make your reviewer guess how things work; wrap it all up for them in a pretty bow.

For example: if you have written a web server which the requirements said should be deployable in Kubernetes, you should:

- Have a note on how the user can get a local kube running (or a link to an existing tutorial)

- Provide the required deployment manifests in your repo, and instructions on how to use or alter them

- Give a list of example requests to run against the server and their expected responses

Make sure your Readme and any documentation you have is well formatted. If you don’t know Markdown, now is your chance to learn.

Final checks

When you are done writing code, have run all the linters and formatters, have checked everything is tidy, have reviewed your commits and made sure your Readme is cute AF, go over everything one last time before you submit. I usually wait until the following day and then spend 15-30 mins checking things with fresh eyes.

- Read the requirements again. Just in case you missed some small detail

- Read through your code again. Read it twice, just to be safe

- Check your Readme for typos

- Check that your example commands are copy-pastable, that they work

- Run your tests

- Make sure it works on a machine other than the one you have been building on. If you don’t have an actual other machine, you can spin up a VM on your current one, or use containers.

As I said waaay at the beginning: reviewing tech tests is very subjective and this advice is all clearly based on what I think qualifies as “good”. Sooo basically it may be useless 😁.

I am trialling different ways of interviewing candidates, as I do think all current processes (including the standard tech test model) are not the best fit for the job. If you or your company are trying new things, or have found something which works well, I would be really happy to hear about it.

If you have found this post useful and would like something in a similar area, drop me an email.

Thanks for reading and good luck with your next job hunt! 🍀