Intro to Test-Driven Development in Golang

To complete this tutorial, you will need to have the following installed:

- Go version >= 1.14

- Git

- A text editor

- A terminal or command prompt (we will be working mainly from the terminal, if you are not comfortable using yours, you may want to complete a Command Line Crash Course before you continue).

Think you are missing something? Check/Install here.

This tutorial assumes you have at least:

- Written a “Hello World!” Go program

- Built and executed that binary on your command line

- … and that’s it! This is a beginner friendly class

Task:

Using TDD, write a program which will help you cheat at the drinking game fizzbuzz.

Rules:

- When the given number is divisible by 3, say fizz

- When the given number is divisible by 5, say buzz

- When the given number is divisible by 3 and 5, say fizzbuzz!

- When the given number does not fit any of the other rules, print the number

What we will be building:

$ go build .

# > creates executable binary/program `fizzbuzz`

$ ./fizzbuzz 3

fizz

$ ./fizzbuzz 5

buzz

$ ./fizzbuzz 15

fizzbuzz!

$ ./fizzbuzz 7

7 :(

Part 1: Project setup

Steps:

-

Open Terminal (or iTerm or whatever else you like to get a command prompt) and create a new directory. Then change into that directory and initialise a new git repository (New to Git? See this guide.):

cd ~ mkdir -p workspace/fizzbuzz cd workspace/fizzbuzz git init git remote add origin <URL OF YOUR REPO ONLINE> echo "tdd exercise in go" > README.md git add README.md git commit -m "readme.md" git push -u origin main -

Initialize your Go project. This is how we store information about which version of Go we are using, and which dependencies our project requires. ‘Dependencies’ are packages (exported and publicly available) written by others which we can use to help build our code. We use

go modto manage them:go mod init github.com/<YOUR USERNAME>/<YOUR PROJECT NAME> # eg: go mod init github.com/callisto13/fizzbuzzYou should end up with a file called

go.modin your repo. -

Install

ginkgoandgomega. Ginkgo is the testing framework we are going to use to write unit tests for our code. Go does have a built-in testing framework, but it is not very user friendly and encourages a style of test-writing which is hard to debug. If testing is too hard then people wont do it, which is bad. Ginkgo and Gomega are Go packages so we need to install them using these twogo getcommands.go get github.com/onsi/ginkgo/ginkgo go get github.com/onsi/gomega/... -

You should notice that your

go.modfile has changed and you now also have ago.sumfile in your repo. -

Check that everything is installed properly by running

ginkgo. This will fail with something likeFound no test suitesand some help on how to run but that is fine. Let’s get testing!

Commit the setup and push to github:

git add go.sum go.mod

git commit -m "setup"

git push

Part 2: Our first test

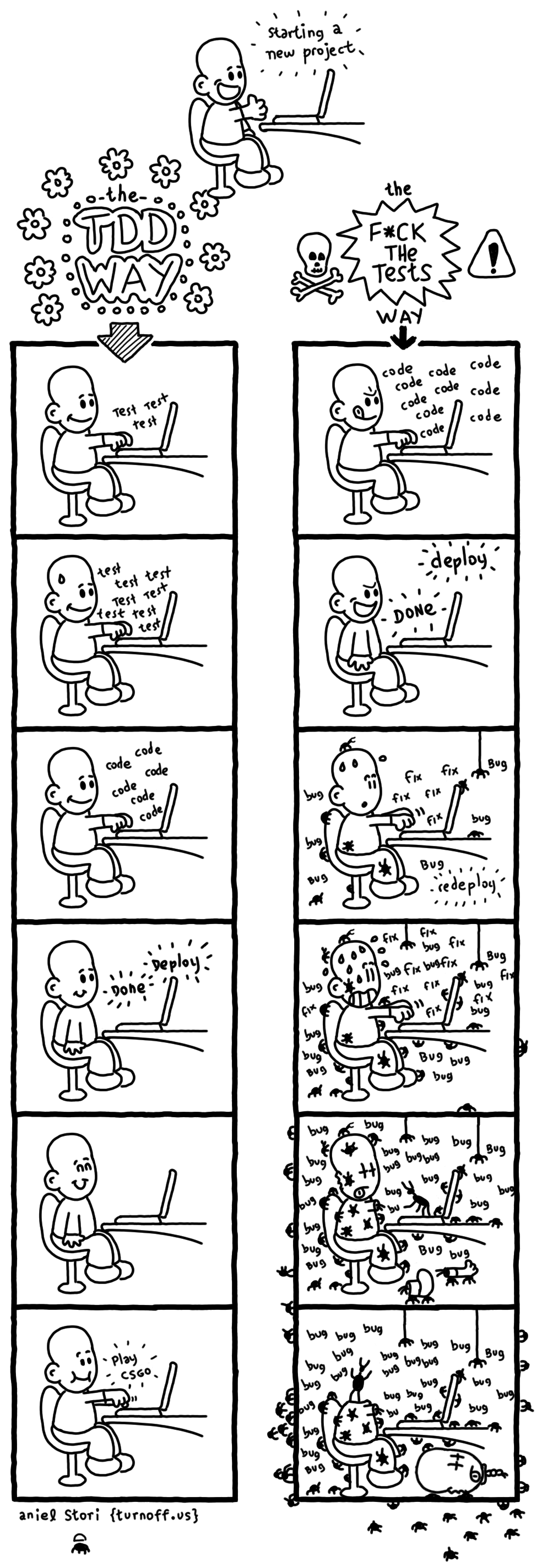

Test Driven Development follows a simple pattern: red -> green -> refactor.

In reality, this works as follows:

- Write a test which would pass if the code was implemented correctly.

- See it fail.

- Write just enough code to make the test pass.

- See the test pass.

- Look over the code and think of ways to improve what you have. Is there any repetition? Can an algorithm be made more efficient?

Writing code this way has 4 benefits: 1) by only writing what you need to achieve basic tasks, you end up writing less code, all of which is used (no ghost functions which you have little memory of); 2) every single function is tested, which makes adding more or changing bits a breeze as you will find out immediately what you may have broken; 3) nicely structured tests makes it easy for others looking at your project to figure out what your code is supposed to do (a good way to get contributors); and 4) because of 1 and 2, you have complete confidence that your code does what it is supposed to do.

So let’s get going with our first test:

Steps:

-

Ginkgo gives us commands which will generate some boilerplate testing code. Run both in your terminal:

ginkgo bootstrap ginkgo generate fizzbuzzThis should generate 2 new files in your repo:

fizzbuzz_suite_test.goandfizzbuzz_test.go.Let’s have a look at those files.

fizzbuzz_suite_test.goshould look something like this:package fizzbuzz_test import ( "testing" . "github.com/onsi/ginkgo" . "github.com/onsi/gomega" ) func TestFizzbuzz(t *testing.T) { RegisterFailHandler(Fail) RunSpecs(t, "Fizzbuzz Suite") }You don’t need too worry to much about what is in this file, since we won’t be touching it again. Let’s quickly go over the highlights.

The first line tells Go that this file is part of the

fizzbuzz_test“package”. A package in Go is like a module: a unit of related code. You can have as many files as you like in the same package, all adding code to the same module. (This doesn’t mean you should throw everything into the same package: the code is supposed to be related. If it is not related, it should go into a different package.)The next section (

import (...)) is where we have specified the other packages that this file need to run: in other words the dependencies for the code in this file. In this case we have"testing", which is Go’s built-in testing framework, and of courseginkgoandgomega. The latter two need to be imported with their full Github module path, since they are not built into the language.testingis which means we need to simply name it.Next we have a Function which is using all three dependencies above to run our test suite.

If we now look at

fizzbuzz_test.go, you should see something like:package fizzbuzz_test import ( . "github.com/onsi/ginkgo" . "github.com/onsi/gomega" . "github.com/<YOUR USERNAME>/fizzbuzz" ) var _ = Describe("Fizzbuzz", func() { })You should recognise the first line (this file is part of the

fizzbuzz_go_testpackage) and theimportsection. We are still depending onginkgoandgomega, but the generator has also anticipated that we will want to import our own package, since that is the code we are going to be testing.Below that is a

Describefunc, in which we will write our first test in a moment.We have to make a small edit to this file before we begin: on the line where your package is imported, remove the

.at the beginning.. "github.com/<YOUR USERNAME>/fizzbuzz" // ^ becomes v, observe the absence of '.' "github.com/<YOUR USERNAME>/fizzbuzz"When we use functions from a package in Go, we do so like this

packagename.FunctionName(). “Dot” imports let you call functions without the package name. We are doing this with Ginkgo and Gomega:Describe("...")could beginkgo.Describe("...")if we removed the.from the start of the line importing it. In the case of those two packages we will keep the “dot” imports, as repeatingginkgo.andgomega.all over our tests will get messy. For our eventual code package, however, we want to be clear that we are using it in our tests. -

Now that we are using some dependencies in our own packages, it is time to save them in a folder called

vendor. This means that we can clone down a new copy of this project anywhere and all the dependencies we need to run it will be included.go mod vendorThis will create a new directory.

You should re-run this command whenever you add a new dependency to any project.

-

Let’s write our first test. Open the

fizzbuzz_test.gofile in your text editor, and alter theDescribefunction, adding the following between the curly braces:var _ = Describe("Fizzbuzz", func() { Context("knows when a number", func() { It("is divisible by 3", func() { }) }) })So what have we done here?

You’ll notice that we haven’t just written

It("works"). TDD is about ensuring that you write your code incrementally by breaking down your problem into small chunks and tackling each problem one at a time. Right now we are writing a pretty simple game, so you may be thinking TDD is overkill, but when it comes to a large project or a very complex problem which you can’t possibly envisage how it will turn out, TDD is a very useful discipline to learn.So let’s read our test.

The first line is to indicate what you are testing. Ginkgo recognises everything within this

Describeblock as the scope of what you want to test. The bit in the quotes is for your benefit: we are testing “Fizzbuzz”. On the next line we define aContext, which does exactly what it sounds like: it gives context to the test, for humans and the compiler. Ginkgo understands that tests under the sameContextare grouped together and share the same state. TheItblock will contain your actual test (right now there is nothing being tested). Likewise the bit in quotes are for your benefit. -

Now we have to state what we expect to happen when a function in our code runs. This is the hardest part of TDD: you have to test code which does not yet exist. But you do know the behaviour you want from it. We have not written a function yet, but we have explained what we want in our test (the

Itquotes), so we know vaguely what it should look like. Put the following line inside the curly braces of yourItblock:It("is divisible by 3", func() { Expect(fizzbuzz.IsDivisibleByThree(3)).To(BeTrue()) }) -

Run the test:

ginkgoThis should fail withgo build github.com/<username>/fizzbuzz: no non-test Go files in <filepath>. Which makes sense; we haven’t written any non-test code yet. Time to write some.

How your project should look at this stage.

Part 3: Make it green

Now that we have our first failing test we are going to follow the errors given by Ginkgo to make it pass.

So let’s start with the first error we were given: no non-test Go files.

Steps:

-

Create and open a new file called

fizzbuzz.go. -

Add the package name to the first line of the file:

package fizzbuzzThis is not a test file, so we don’t need to end the package name with the

_testidentifier. -

If we run the test again (

ginkgo), we see that we have moved on to the next error:Failed to compile fizzbuzz: # github.com/<username>/fizzbuzz_test [github.com/<username>/fizzbuzz.test] ./fizzbuzz_test.go:12:10: undefined: fizzbuzz.IsDivisibleByThree Ginkgo ran 1 suite in 2.140132121s Test Suite Failed -

In

fizzbuzz.godefine that function which Ginkgo was complaining about. Don’t make it do anything, just define it:func IsDivisibleByThree(number int) bool { return false }Here we have defined the function we we promised the test would exist. It takes on argument (in the test this is

3) which is a type ofint(integer/number) and we give it a namenumberso that it can be used within the function.The return value is a

boolmeaning that the output of this function will be eithertrueorfalse.Lastly we are simply returning

falseas a default, since Go requires that if your function says something will be returned, something actually is. -

Save the files and run the test again:

ginkgo. Now we should see something more like a test:Running Suite: Fizzbuzz Suite ============================= Random Seed: 1586604740 Will run 1 of 1 specs • Failure [0.001 seconds] FizzbuzzGo /.../fizzbuzz/fizzbuzz_test.go:10 knows when a number is divisible by 3 [It] /.../fizzbuzz/fizzbuzz_test.go:11 Expected <bool>: false to be true /.../fizzbuzz/fizzbuzz_test.go:12 ------------------------------ Summarizing 1 Failure: [Fail] FizzbuzzGo [It] knows when a number is divisible by 3 /.../fizzbuzz/fizzbuzz_test.go:12 Ran 1 of 1 Specs in 0.001 seconds FAIL! -- 0 Passed | 1 Failed | 0 Pending | 0 Skipped --- FAIL: TestFizzbuzz (0.00s) FAIL Ginkgo ran 1 suite in 1.513106767s Test Suite FailedExcellent! We have told our test that when function

IsDivisibleByThreereceives the number3, the answer should betrue. So let’s go give it what it wants. -

Go back to

fizzbuzz.goand makeIsDivisibleByThreereturntruefunc IsDivisibleByThree(number int) bool { return true } -

Run the test again. And we’re green! Congrats, you have passed your first test. Let’s go wreck it.

How your project should look at this stage.

Part 4: Make it red

Obviously we are not done yet. Hardcoding true like that is seen as a Very

Bad Thing, and also not very useful for our game. So let’s write another test

to force ourselves to do the right thing.

Steps:

-

In

fizzbuzz_test.goadd a secondItblock under the first. (Make sure you stay in the sameContextblock.)It("is NOT divisible by 3", func() { Expect(fizzbuzz.IsDivisibleByThree(1)).To(BeFalse()) }) -

Run the tests again. Back to red?

1 Passed, 1 Failed?Expected: true to be false? Excellent. Time for some maths. -

Back in

fizzbuzz.gowe need to make our function work out whether thenumit is being passed as an argument (which right now we are ignoring) is actually divisible by three. To do that we need to use modular arithmetic: ifnumcan be evenly divided by 3, it should return 0 (i.e. not have a remainder).func IsDivisibleByThree(number int) bool { if num%3 == 0 { return true } return false } -

Now when we run the tests, both should pass. We don’t have much code right now, but there is already some refactoring to be done. There is a way to write that bit of

ifandreturnlogic on just one line rather than 4. If you can figure it out, update your function to be less verbose. (Don’t forget to make sure your tests still pass after you change things!)

We added a bunch of new stuff, so let’s commit in stages to keep things tidy.

First let’s commit the vendor dir and module files:

git add go.mod go.sum vendor

git commit -m "vendor dependencies"

And then our code and tests:

git add fizzbuzz.go fizzbuzz_test.go fizzbuzz_suite_test.go

git commit -m "knows when a number is divisible by 3"

git push

How your project should look at this stage.

Part 5: Around we go again…

Steps:

-

In

fizzbuzz_test.go, add anotherItblock (again still within the sameContextblock) to test whether numbers are divisible by 5:It("is divisible by 5", func() { Expect(fizzbuzz.IsDivisibleByFive(5)).To(BeTrue()) }) -

Run the tests. Do you see

Failed to compile fizzbuzz-go:... undefined: fizzbuzz.IsDivisibleByFive? -

Go define

IsDivisibleByFiveinfizzbuzz.go. (just define and set a default, don’t make it do anything.) -

Run the tests.

Expected: false to be true? Make your new function returntrue. -

Run the tests. Green again? Go back to your test file and write the opposing

It('is NOT divisible by 5'block. -

Run the tests.

Expected: true to be false? Fix your code with modular arithmetic to make it pass.

Once you have all 4 tests passing, commit your work and push to github:

git add fizzbuzz.go fizzbuzz_test.go

git commit -m "knows if numbers are divisible by 5"

git push

2 functions in and we are starting to see a pattern here, but let’s leave off

refactoring just a little while longer and move onto the last calculation.

By now you should know the routine, so go ahead and write 2 more tests for a function

which knows if a number IsDivisibleByThreeAndFive. (Hint: you can use just one number to do this division.)

Once you have all 6 tests passing, commit your work and push to github:

git add fizzbuzz.go fizzbuzz_test.go

git commit -m "knows if numbers are divisible by 3 and 5"

git push

How your project should look at this stage.

Part 6: First Refactor

Right now we have three functions which are doing more or less the same thing. Let’s see if we can DRY this out a bit.

-

In

fizzbuzz.go, edit your code so that the 3IsDivisibleBy*functions are replaced by just 1 function.func IsDivisibleBy(number, divisor int) bool { return number%divisor == 0 } -

Run your tests. Are they very unhappy? Update them to use the new function. If you are having trouble making them pass, remember to read the failure messages carefully: Ginkgo is helpful and will generally point you in the right direction.

Once you are all green again, commit your work and push to github:

git add fizzbuzz.go fizzbuzz_test.go

git commit -m "first refactor"

git push

How your project should look at this stage.

Part 7: FizzBuzz says

So now our code can tell us whether a number is divisible by 3, 5 or 3 and 5, but we can’t really play the game with this.

Steps:

-

In

fizzbuzz_test.godefine a newContextblock underneath the end of the old one, still within the sameDescribeblock.Context("when playing the game, Fizzbuzz says...", func() { It("`fizz` when a number is divisible by 3", func() { }) }) -

Next, put what you would expect to happen inside your

Itblock:Context("when playing the game, Fizzbuzz says...", func() { It("`fizz` when a number is divisible by 3", func() { Expect(fizzbuzz.Says(3)).To(Equal("fizz")) }) }) -

Run your tests. They should fail in a way which by now should be familiar.

-

Go into

fizzbuzz.goand create that function. (just define, and return a default empty string"".) -

Run the tests again and follow the error message, remember to do just enough to make them pass:

func Says(number int) string { return "fizz" } -

Add the next test within that

Contextto force yourself to write code which actually evaluates something.It("`buzz` when a number is divisible by 5", func() { Expect(fizzbuzz.Says(5)).To(Equal("buzz")) }) -

See the test fail, then go back to your code and make your new function process the argument it is passed by using our

IsDivisibleByfunction:func Says(number int) string { switch { case IsDivisibleBy(number, 3): return "fizz" case IsDivisibleBy(number, 5): return "buzz" } return "" } -

Go back to

fizzbuzz_test.go, and add the test which check that the program says “fizzbuzz” when a number is divisible by 3 and 5. -

Run the tests, watch it fail.

-

Go to your code and make it pass.

note: remember to watch your ordering here. Since you are returning immediately when the number is first sucessfully divisible, you may end up saying “fizz” rather than “fizzbuzz”. Make sure you check if a number can be divisible by 3 and 5 first. Switch the order of your code to see your tests failing in this way.

-

The last thing we need to do is write a test (and then the code) for when the number is not divisible by 3, 5 or 3 and 5. It should just return the number.

Once you have all 10 tests passing, commit your work and push to github:

git add fizzbuzz.go fizzbuzz_test.go

git commit -m "returns fizz, buzz and fizzbuzz"

git push

How your project should look at this stage.

Bonus round! Trickier stuff ahead.

All our calculations are done and we are ready to play the game… but it doesn’t

quite work in the way we planned at the start. We can’t do $ ./fizzbuzz 3

and expect to see fizz in the terminal right now.

So, for bonus points, we are going to write some integration tests. Up to now we have

been testing out each individual unit of code in… unit tests (obvs). Now we

need to verify that our code integrates with the tools which are not directly part of that code

but are going to interact with it (in this case the command line).

Part 8: Building an executable

Steps:

-

First let’s do some tidying up. Create a new directory in your project and move your existing Go files in there:

mkdir -p pkg/fizzbuzz mv fizzbuzz.go fizzbuzz_test.go fizzbuzz_suite_test.go pkg/fizzbuzzThis will break your tests (remember those

importpaths?) so open uppkg/fizzbuzz/fizzbuzz_test.goto update the import to the new location:"github.com/<username>/fizzbuzz/pkg/fizzbuzz"Check that everything is back to normal by running the tests. This time you will need to change the test command to

ginkgo -rthe-rmeans recursive, as in “look for all test files in all directories from here”. -

Once you have verified that your old tests still run, we can set up the new ones. Create a new directory in your project:

mkdir integrationYour project layout should now look like this:

. ├── go.mod ├── go.sum ├── integration ├── pkg │ └── fizzbuzz │ ├── fizzbuzz.go │ ├── fizzbuzz_suite_test.go │ └── fizzbuzz_test.go └── vendorChange into the new

integrationdirectory.cd integrationAnd run the Ginkgo generation commands:

ginkgo bootstrap ginkgo generate integrationLike before, this will create 2 new test files:

integration_test.goandintegration_suite_test.go.Move back out of this new directory when you are done generating the files.

cd .. -

Open

integration_test.goin your text editor.In these tests we need to compile the

fizzbuzzbinary, execute it, and verify that the correct answer is printed out.Fortunately, Ginkgo can help us with that.

Remove everything currently in

integration_test.goand replace it with the following. There is a lot going on here so I have added comments over the key bits.package integration_test import ( // the package which will let us execute the binary from here "os/exec" . "github.com/onsi/ginkgo" . "github.com/onsi/gomega" // the packages that we need to build the binary and check output // in the test "github.com/onsi/gomega/gexec" "github.com/onsi/gomega/gbytes" ) var _ = Describe("Integration", func() { // these are declared here so they can be used throughout the test file var ( fizzbuzzBinary string fizzbuzzCommand *exec.Cmd ) // a helper function to set things up before the actual tests run BeforeEach(func() { var err error // compile the fizzbuzz binary // swap callisto13 for your username. this string should // match the module name in your go.mod fizzbuzzBinary, err = gexec.Build("github.com/callisto13/fizzbuzz", "-mod=vendor") // verify that compilation did not fail Expect(err).NotTo(HaveOccurred()) }) // a helper function to delete the compiled binary after tests have run AfterEach(func() { gexec.CleanupBuildArtifacts() }) It("when the command line argument is 3, it prints 'fizz'", func() { // get the command ready, passing in 3 as an argument fizzbuzzCommand = exec.Command(fizzbuzzBinary, "3") // run the command session, err := gexec.Start(fizzbuzzCommand, GinkgoWriter, GinkgoWriter) // verify that it did not fail Expect(err).NotTo(HaveOccurred()) // verify that it has printed the right thing to the terminal (stdout) Eventually(session.Out).Should(gbytes.Say("fizz\n")) }) }) -

After you have copied this, you can run the test:

ginkgo -r(orginkgo -r integrationif you only want to run the new tests).They should fail with something like

cannot load <package>: no Go source files. This is because we are missing amain.gofile: the entry point to our binary.At the base of your project, create a

main.gofile. Your layout should now look like this:. ├── go.mod ├── go.sum ├── integration │ ├── integration_suite_test.go │ └── integration_test.go ├── main.go ├── pkg │ └── fizzbuzz │ ├── fizzbuzz.go │ ├── fizzbuzz_suite_test.go │ └── fizzbuzz_test.go └── vendorOpen it up and paste the following into your

main.go:package main func main() { }Now when you run the test again, it should complain that it is stuck waiting for “fizz”.

-

This is easy to fix, update your

mainfunc to print the string the test expects:package main import "fmt" // don't forget to import new packages func main() { fmt.Println("fizz") }The test passes, and although the binary is still useless, it’s a good time to commit what we have so far.

git add pkg/ integration/ main.go

# you need to git add the moved files so that git picks up the change

git add fizzbuzz.go fizzbuzz_test.go fizzbuzz_suite_test.go

git commit -m "integration test setup and restructuring"

We have also started using more of the Gomega dependency in our integration test.

When you vendor a dependency, only the files you are actually using from those

packages are saved, so we need to re-vendor to ensure that the new gomega files

or subpackages (in this case gexec and gbytes) are included.

go mod vendor # save all in-use dependencies to vendor/

go mod tidy # ensure duplicated dependencies and removed and go.sum is up to date

Then we can commit:

git add vendor/ go.sum

git commit -m "update dependencies"

git push

How your project should look at this stage.

Part 9: Command line args

-

We have hardcoded the output in main, which is fine for our current test. Let’s add another

Itunder the last to force us to use thefizzbuzzpackage we wrote earlier:It("when the command line argument is 5, it prints 'buzz'", func() { fizzbuzzCommand = exec.Command(fizzbuzzBinary, "5") session, err := gexec.Start(fizzbuzzCommand, GinkgoWriter, GinkgoWriter) Expect(err).NotTo(HaveOccurred()) Eventually(session.Out).Should(gbytes.Say("buzz\n")) })This test should fail, as our binary only prints “fizz”. Let’s make our main recognise command line args, and use our code.

-

Open

main.goand update our main func with the following:package main import ( "fmt" "os" "strconv" "github.com/callisto13/fizzbuzz/pkg/fizzbuzz" ) func main() { // get the first command line argument numberAsString := os.Args[1] // the argument comes in as a string, so we need to turn it into an integer number, _ := strconv.Atoi(numberAsString) // call our package and print the result to stdout fmt.Println(fizzbuzz.Says(number)) }Now both our integration tests pass: our program can be built and executed with args from the command line!

git add integration/integration_test.go main.go

git commit -m "can be run from the command line"

git push

How your project should look at this stage.

Part 10: Error handling

-

We are not done yet. Did you notice that when we convert the argument from a string to an int that we are ignoring a return value? That value is an error, and we want to catch and process that before it gets used by our package.

Lets write a new test to verify we do the right thing when something which is not a number is passed to our program.

It("when the command line argument is not a number, it prints an error", func() { fizzbuzzCommand = exec.Command(fizzbuzzBinary, "!") session, err := gexec.Start(fizzbuzzCommand, GinkgoWriter, GinkgoWriter) Expect(err).NotTo(HaveOccurred()) Eventually(session.Out).Should(gbytes.Say("arguments must be numbers\n")) })When we run the test, it fails. The conversion in main failed and set

numberto0which means that when our package processes it, it will return “fizzbuzz”.0%15is0so our package is technically correct, but this is not the behaviour we want: our users shouldn’t be able to pass nonsense to our game and get “fizzbuzz”. -

Update the main func to catch non-number args:

number, err := strconv.Atoi(numberAsString) if err != nil { fmt.Println("arguments must be numbers") // exit the program here os.Exit(1) }Our integration test should now pass.

If you want, you can add some extra handling (and tests) in

pkg/fizzbuzzto deal with inputs being0.

Commit and push this stage:

git add integration/integration_test.go main.go

git commit -m "program errors when passed a non-number arg"

git push

Part 11: Multiple Args

Currently we can pass a single arg to our binary on the command line, but it would be nice if we could pass a series of numbers:

./fizzbuzz 1 2 3 4 5

1

2

fizz

4

buzz

-

As usual, let’s start by adding a new integration test:

It("when there are several command line argument, it processes them all", func() { args := []string{"1", "2", "3", "4", "5"} fizzbuzzCommand = exec.Command(fizzbuzzBinary, args...) session, err := gexec.Start(fizzbuzzCommand, GinkgoWriter, GinkgoWriter) Expect(err).NotTo(HaveOccurred()) Eventually(session.Out).Should(gbytes.Say("1\n2\nfizz\n4\nbuzz\n")) }) -

And I will leave it to you to update

main.goto handle this and make the test pass.

Once you have all tests passing, commit your work and push to github:

git add integration/integration_test.go main.go

git commit -m "can receive multiple args"

git push

Part 12: Zero args

Lastly we need to handle a user passing in no arguments at all. Currently nothing happens, but it would be cool if there was some nice user feedback, explaining how to use the program.

- Write your test.

- Update the code to make it pass.

- Commit your changes.

Part 13: Tidying up

Take a look through your code. Is there any tidying up or refactoring we could do?

What about the tests? There is a little repetition, is there a way you can use

BeforeEach and JustBeforeEach or other such blocks to remove some of this? Check out the

Ginkgo docs to learn more.

Remember to run your tests frequently as you make changes so that you do not accidentally break anything. This is what they are for.

How your project could look at this stage.

WooHoo!!

And that’s it! You just test-drove your first Go program.

But don’t stop there; test-driven development is a good habit to get into and the majority of (sensible) companies value it very highly. Think back to small programs you have written and see if you can do them again through TDD. Or test drive out another simple game or calculator (Leap Year, maybe?).

There is a testing framework (often much more than one) for every language, so go ahead and play Fizzbuzz again in the one of your choice.

In fact, small exercises like Fizzbuzz are a great way to get to grips with a new language and its testing framework; it’s my personal goto for the first thing I write in whatever new thing I am trying. (Many companies also use it to test interview candidates.)

At some point I will be going on to write another, more challenging TDD tutorial so watch this space. :)

In the meantime, check out Exercism for more TDD practice.