Intro to Test-Driven Development in NodeJS

To complete this tutorial, you will need to have the following installed:

- Node

- Git

- A text editor

- A terminal or command prompt (we will be working mainly from the terminal, if you are not comfortable using yours, you may want to complete a Command Line Crash Course before you continue).

Think you are missing something? Check/Install here.

Task:

Using TDD, write a program which will help you cheat at the drinking game fizzbuzz.

Rules:

- When the given number is divisible by 3, say fizz

- When the given number is divisible by 5, say buzz

- When the given number is divisible by 3 and 5, say fizzbuzz!

- When the given number does not fit any of the other rules, print the number

$ node fizzbuzz.js 3

fizz

$ node fizzbuzz.js 5

buzz

$ node fizzbuzz.js 15

fizzbuzz!

$ node fizzbuzz.js 7

7 :(

Part 1: Project setup

Steps:

-

Open Terminal (or iTerm or whatever else you like to get a command prompt) and create a new directory. Then change into that directory and initialise a new git repository (New to Git? See this guide.):

cd ~ mkdir -p workspace/fizzbuzz cd workspace/fizzbuzz git init git remote add origin <URL OF YOUR REPO ONLINE> echo "tdd exercise in node" > README.md git add README.md git commit -m "readme.md" git push -u origin main -

Initialize your

node_modules. This is where we store the dependencies we want our program to use. ‘Dependencies’ are packages (exported and publicly available) written by others which we can use to help build our code. We usenpmto manage them:npm initHit enter/return to any questions that are asked. You should end up with a file called

package.jsonin your repo. -

Git ignore your

node_modules. When we install new dependencies they can end up taking up a lot of room in our git repo. This is not a nice thing to push to the cloud as it slows everything down. Since yourpackage.jsonandpackage-lock.jsonwill hold a record of all your dependencies, you don’t need to commit the actual folders at all, so it is safe to ignore them. Create a new file called.gitignore(the.means it is hidden, so you won’t see it with a plain oldls), at put the following inside:node_modules/Save and quit.

-

Install

jest. Jest is the testing framework we are going to use to write unit tests for our code. Jest is a node package so we need to install it using thenpmcommand.npm install --save-dev jest -

Open your

package.jsonin a text editor and update it to refer tojestas the testing framework. Change the following line from"test": "echo \"Error: no test specified\" && exit 1", to:... "scripts": { "test": "jest" }, ... -

Check that everything is installed properly by running

npm run test. This will fail with something likeNo tests foundand lots of redERR!but that is fine. Let’s get testing!

Commit the setup and push to github:

git add package.json package-lock.json .gitignore

git commit -m "setup"

git push

Part 2: Our first test

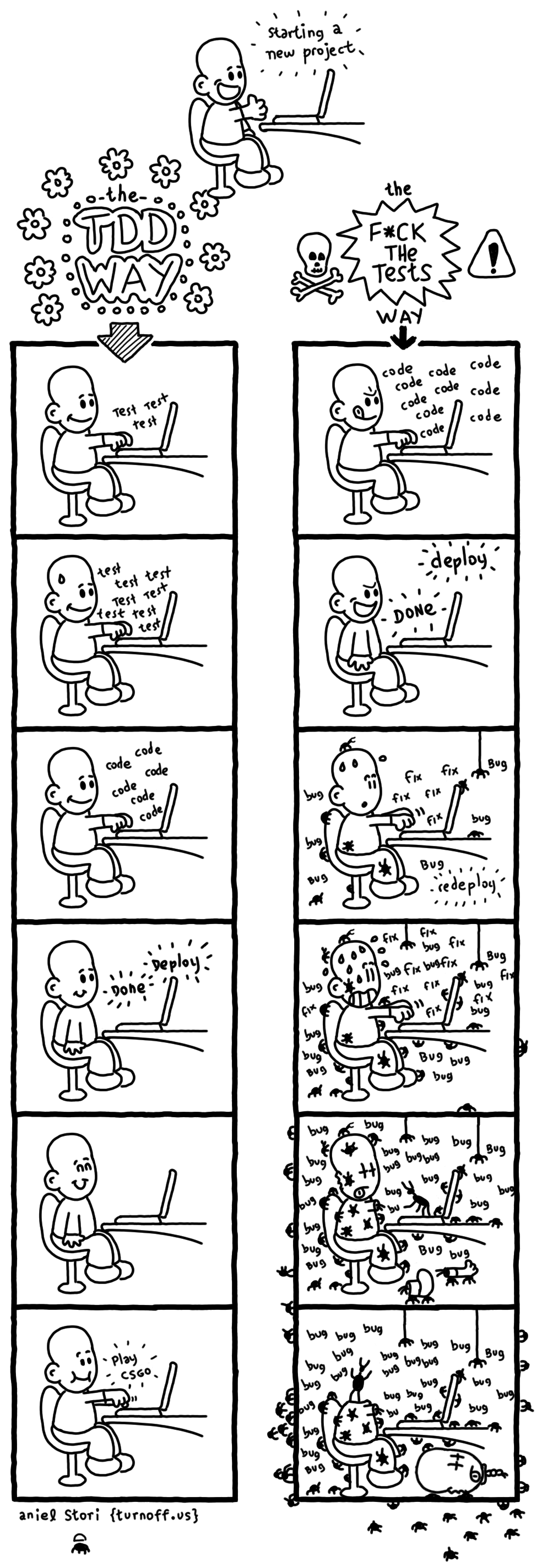

Test Driven Development follows a simple pattern: red -> green -> refactor.

In reality, this works as follows:

- Write a test which would pass if the code was implemented correctly.

- See it fail.

- Write just enough code to make the test pass.

- See the test pass.

- Look over the code and think of ways to improve what you have. Is there any repetition? Can an algorithm be made more efficient?

Writing code this way has 4 benefits: 1) by only writing what you need to achieve basic tasks, you end up writing less code, all of which is used (no ghost functions which you have little memory of); 2) every single function is tested, which makes adding more or changing bits a breeze as you will find out immediately what you may have broken; 3) nicely structured tests makes it easy for others looking at your project to figure out what your code is supposed to do (a good way to get contributors); and 4) because of 1 and 2, you have complete confidence that your code does what it is supposed to do.

So let’s get going with our first test:

Steps:

-

Create a new file called

fizzbuzz.spec.js. -

Open the project in your text editor, and write the following to it:

describe('Fizzbuzz', () => { test('knows when a number is divisible by 3',() => { }); });So what have we done here?

You’ll notice that we haven’t just written

test('it works'). TDD is about ensuring that you write your code incrementally by breaking down your problem into small chunks and tackling each one at a time. Right now we are writing a pretty simple game, so you may be thinking TDD is overkill, but when it comes to a large project or a very complex problem which you can’t possibly envisage how it will turn out, TDD is a very useful discipline to learn.So let’s read our test.

The first line is to indicate what you are testing. The jest program recognises everything within this

describeblock as the scope of what you want to test. The bit in the quotes is for your benefit. Jest understands that tests under the samedescribeare grouped together and share the same state. Thetestblock will contain your test (right now there is nothing actually being tested). -

Now we have to state what we expect to happen when a function in our code runs. We have not written a function yet, but we have explained what we want in our test, so we know vaguely what it should look like. Put the following line inside your

testblock:test('knows when a number is divisible by 3',() => { expect(fizzbuzz.isDivisibleByThree(3)).toBeTruthy(); }); -

Run the test:

npm run testThis should fail with quite a lot of noise, but if you scroll up a little you should see something likeReferenceError: fizzbuzz is not defined. Which makes sense; we haven’t defined any functionality anywhere. Time to write some code.

How your project should look at this stage.

Part 3: Make it green

Now that we have our first failing test we are going to follow the errors given by jest to make it pass.

So let’s start with the first error we were given: ReferenceError: fizzbuzz is not defined.

Steps:

-

Create and open a new file called

fizzbuzz.js. -

Define that function which jest was complaining about. Don’t make it do anything, just define it:

function isDivisibleByThree(number) { } -

Save the file and run the test again. Same thing? What are we missing? Does our test file know where our code is or how to find functions? In Node we need to

exportour functions where we define them and then import them where we use them. So we can add our new functions to the exported modules by adding the bottom tofizzbuzz.js:module.exports = { isDivisibleByThree: isDivisibleByThree }And at the top of fizzbuzz.spec.js add:

const fizzbuzz = require('./fizzbuzz'); -

Save the files and run the test again:

npm run test. Now we should see something new:Fizzbuzz ✕ knows when a number is divisible by 3 (10ms) ● Fizzbuzz › knows when a number is divisible by 3 expect(received).toBeTruthy() Received: undefinedThat is admittedly a very unhelpful error (javascript is great at unhelpful errors), but we can make a guess: Our test is expecting our function to return

truebut it is gettingundefinedor nothing. So let’s go give it what it wants. -

Go back to

fizzbuzz.jsand makeisDivisibleByThreereturntruefunction isDivisibleByThree(number) { return true; } -

Run the test again. And we’re green! Congrats, you have passed your first test. Let’s go wreck it.

How your project should look at this stage.

Part 4: Make it red

Obviously we are not done yet. Hardcoding true like that is seen as a Very

Bad Thing, and also not very useful for our game. So let’s write another test

to force ourselves to do the right thing.

Steps:

-

In

fizzbuzz.spec.jsadd a secondtestblock under the first. (Make sure you stay in the samedescribeblock.)test('knows when a number NOT is divisible by 3',() => { expect(fizzbuzz.isDivisibleByThree(1)).toBeFalsy(); }); -

Run the tests again. Back to red?

1 failed, 1 passed?Received: truewhen expected falsy? Excellent. Time for some maths. -

Back in

fizzbuzz.jswe need to make our function work out whether thenumberit is being passed as an argument (which right now we are ignoring) is actually divisible by three. To do that we need to use modular arithmetic: ifnumbercan be evenly divided by 3, it should return 0 (i.e. not have a remainder).function isDivisibleByThree(number) { if (number % 3 === 0) { return true; } } -

Now when we run the tests, both should pass. Seeing as we have very little code right now, there is no refactoring to be done so we can go on to writing more tests.

How your project should look at this stage.

Commit this stage and push to github:

git add fizzbuzz.js fizzbuzz.spec.js

git commit -m "knows when a number is divisible by 3"

git push

Part 5: Around we go again…

Steps:

-

In

fizzbuzz.spec.js, add anothertestblock (again still within the samedescribeblock) to test whether numbers are divisible by 5:test('knows when a number is divisible by 5',() => { expect(fizzbuzz.isDivisibleByFive(5)).toBeTruthy(); }); -

Run the tests. Do you see

TypeError: fizzbuzz.isDivisibleByFive is not a function? -

Go define

isDivisibleByFiveinfizzbuzz.js. (just define, don’t make it do anything.) Don’t forget to ensure your new function is also listed underisDivisibleByThreeinside themodules.exportsbrackets. (Hint: you will need to add a comma (,) afterisDivisibleByThree.) -

Run the tests.

Received: undefined? Make your function returntrue. -

Run the tests. Green again? Go back to your test file and write the opposing

test('is NOT divisible by 5'block. -

Run the tests.

Received: true? Fix your code to make it pass.

Once you have all 4 tests passing, commit your work and push to github:

git add fizzbuzz.js fizzbuzz.spec.js

git commit -m "knows if numbers are divisible by 5"

git push

2 functions in and we are starting to see a pattern here, but let’s leave off

refactoring just a little while longer and move onto the last calculation.

By now you should know the routine, so go ahead and write 2 more tests for a function

which knows if a number isDivisibleByThreeAndFive. (Hint: you can use just one number to do this division.)

Once you have all 6 tests passing, commit your work and push to github:

git add fizzbuzz.js fizzbuzz.spec.js

git commit -m "knows if numbers are divisible by 3 and 5"

git push

How your project should look at this stage.

Part 6: First Refactor

Right now we have three functions which are doing more or less the same thing. Let’s see if we can DRY this out a bit.

-

In

fizzbuzz.js, edit your code so that the 3isDivisibleBy*functions are replaced by just 1 function.function isDivisibleBy(number, divisor) { if (number % divisor == 0) { return true; } }And the

module.exportsshould now just be:module.exports = { isDivisibleBy: isDivisibleBy }; -

Run your tests. Are they very unhappy? Update them to use the new function. If you are having trouble making them pass, remember to read the failure messages carefully: jest is helpful and will generally point you in the right direction.

Once you are all green again, commit your work and push to github:

git add fizzbuzz.js fizzbuzz.spec.js

git commit -m "first refactor"

git push

How your project should look at this stage.

Part 7: FizzBuzz says

So now our code can tell us whether a number is divisible by 3, 5 or 3 and 5, but we can’t really play the game with this.

Steps:

-

In

fizzbuzz.spec.jsdefine a newdescribeblock underneath theendof the old one.describe('When playing the game, fizzbuzz says...', () => { test('"fizz" when a number is divisible by 3',() => { }); }); -

Next, put what you would expect to happen inside your

testblock:test('"fizz" when a number is divisible by 3',() => { expect(fizzbuzz.says(3)).toEqual('fizz'); }); -

Run your tests. They should fail in a way which by now should be familiar.

-

Go into

fizzbuzz.jsand create that function. (just define. don’t implement.) Don’t forget to ensure your new function is listed underisDivisibleByinside themodules.exportsbrackets. (Hint: you will need to add a comma (,) afterisDivisibleBy.) -

Run the tests again and follow the error message, remember to do just enough to make them pass:

function says(number) { return "fizz"; } -

Add the next test to force yourself to write code which actually evaluates something.

test('"buzz" when a number is divisible by 5',() => { expect(fizzbuzz.says(5)).toEqual('buzz'); }); -

See the test fail, then go back to your code and make your new function process the argument it is passed by using our

isDivisibleByfunction:function says(number) { if (isDivisibleBy(number, 3) === true) { return "fizz"; } if (isDivisibleBy(number, 5) === true) { return "buzz"; } } -

Go back to

fizzbuzz.spec.js, and add the test which check that the program says “fizzbuzz” when a number is divisible by 3 and 5. -

Run the tests, watch it fail.

-

Go to your code and make it pass.

note: remember to watch your ordering here. Since you are returning immediately when the number is first sucessfully divisible, you may end up saying “fizz” rather than “fizzbuzz”. Make sure you check if a number can be divisible by 3 and 5 first. Switch the order of your code to see your tests failing in this way.

-

The last thing we need to do is write a test (and then the code) for when the number is not divisible by 3, 5 or 3 and 5. It should just return the number.

Once you have all 10 tests passing, commit your work and push to github:

git add fizzbuzz.js fizzbuzz.spec.js

git commit -m "says fizz, buzz and fizzbuzz"

git push

How your project should look at this stage.

Part 8: Bonus Round

All our calculations are done and we are ready to play the game… but it doesn’t

quite work in the way we planned at the start. We can’t do $ node fizzbuzz.py 3

and expect to see fizz in the terminal right now.

So, for bonus points, you are going to write some integration tests. Up to now we have

been testing out each individual unit of code in… unit tests (obvs). Now we

need to verify that our code integrates with the tools which are not directly part of that code

but are going to interact with it (in this case the command line).

You would normally write your integration tests in a separate place (the code too, but for this you can ignore that),

so start by creating an integration.spec.js file and setting up the file in the same

way as we did last time.

In fizzbuzz.js you will need to find a way to get the command line arguments

and pass them to your says function.

You will also need to find a way of executing your game from inside a test file. Here is one possible way, but there are others so take some time to look around.

Drive out your code the same way as you did above: describe the first simple thing

you expect to happen, do just enough to make it pass, then move onto the next simple thing.

Remember to follow the errors returned by npm run test; oftentimes the answers will be there.

To make our game work properly, we want to make sure that:

- Our code can be executed (successfully).

- The result will be printed to terminal output (

stdout). - We can pass multiple arguments and see them all processed (

node fizzbuzz 1 2 3should print1 2 fizz).

Once you have all tests passing, commit your work and push to github:

git add fizzbuzz.js fizzbuzz.spec.js integration.spec.js

git commit -m "can be run from the command line"

git push

WooHoo!!

And that’s it! You just test-drove your first program.

But don’t stop there; test-driven development is a good habit to get into and the majority of (sensible) companies value it very highly. Think back to small programs you have written and see if you can do them again through TDD. Or test drive out another simple game or calculator (Leap Year, maybe?).

There is a testing framework (often much more than one) for every language, so go ahead and play Fizzbuzz again in the one of your choice.

In fact, small exercises like Fizzbuzz are a great way to get to grips with a new language and its testing framework; it’s my personal goto for the first thing I write in whatever new thing I am trying.

At some point I will be going on to write another, more challenging TDD tutorial so watch this space. :)

In the meantime, check out Exercism for more TDD practice.